Erick Ybarra © November 5th, 2021

This post will be aimed at answering the following objections:

- Pope Hadrian was simply using “empty honorifics” that had no “application in reality”. Therefore, his letters contain nothing of semblance to the Papal claims of Vatican 1.

- Charlemagne and the Libri Carolini (Books of Charles or Charlemagne), both which contain glowing honorific descriptions of the Apostolic See of Rome, rejected the 2nd Council of Nicaea and Pope Hadrian’s theological defense of icon veneration. This shows that glowing praise of the authority of the Apostolic See is an empty honorific the lacks any application towards real decision-making.

- The 2nd Council of Nicaea’s ignoring and rejecting the Pope’s demand for a return of the Petrine patrimonies of Sicily and Calabria (funds for candle-making and distribution to the poor), as well as the refusal to return Rome’s Patriarchal supervision of the same territories as well as the prefecture of Illyricum (Greece, Macedonia, Thessaloniki) shows that the Pope had no authority in the matter, and therefore doesn’t have universal and immediate jurisdiction

- The 2nd Council of Nicaea’s use of the famous Matthean Tu es Petrus (Matt 16:18-19) citation applies to the whole Church, and not only Rome, showing that, in reality, they had no belief in a Petrine supremacy individuated uniquely to the bishop of Rome.

- The 7th session of the 2nd Council of Nicaea says that the mere “cooperation” of the Roman Church is needed alongside the “assent” of all the other Patriarchs for a Council, duly convened by the Roman Emperor, to be ranked Ecumenical. This contradicts the Vatican 1 teaching that an Ecumenical Council merely needs the ratification of the Pope.

- The Greek version of Pope Hadrian’s letter to the Emperors says that all Bishops succeed to the pastoral commission of the Matthean Tu es Petrus (Matt 16:18-19) because it says that all those who succeed to “their thrones” (plural), indicating that it is not just Rome that perpetuates that commission, but every successor to the Apostles.

- The letter of Pope Hadrian to Tarasios, which does not delete its Papal claims, are not congruent with the claims made in the Latin version of Hadrian’s letter to the Emperors, and therefore the former does not contain anything intolerable to Byzantine ears like the latter did.

- [Above summarized from Orthodox Craig Truglia who provided content: see link, link, and link]

Preliminary Remarks

One of the most common mistakes made in pursuit to test the evidence of the Papacy in the early Church throughout the 1st millennium is when the researcher has an unreasonable criterion for what amounts to evidence. Some have the expectation that every piece of the evidence must contain the full-blown content of what is defined at the 1st Vatican Council on the primacy and authority of Peter and his successors. Still others believe, more radically, that the 1st Vatican Council simply teaches that the Pope is invincibly infallible, and that Councils are ecumenical simply because he says so. Some have this idea that the magisterial government of the Pope is like adding extra pages to the Holy Bible in human form. With such an overblown understanding of the Papacy, it is no wonder that many go into history and find next to nothing in support of it. The best remedy for this is for folks to purchase the decrees of the 1st Vatican Council and read them carefully in a reliable translation. I recommend McNabb, V. (Ed.), The Decrees of the Vatican Council (New York: Benziger Brothers, 1907). It is crucial that we understand that the Vatican Council’s dogmatic constitution on Papal authority is an elaborate argument that builds through an organic development of the idea of the primacy of St. Peter.

In this presentation, all that is found to be taught from the 2nd Council of Nicaea is that data that Christ divinely singled out Peter and gave him a unique power to govern the universal Church, and that this pastoral commission and prerogative of power is inherited by Peter’s successors in the Roman bishopric until the consummation of all things. This simpler idea is evidenced in the Acts of the Council, and it is the foundation for the more developed definition of Papal authority in the 19th century. Now, that data does not explicitly say anything about Papal infallibility, however much it might be implied. Moreover, 2nd Nicaea does not “formally teach” anything about the rights and nature of Papal authority. Therefore, to the question, “Does 2nd Nicaea teach Papal supremacy and infallibility?”, a Catholic may answer in the negative. The first Council that formally teaches upon the nature of the Petrine primacy in Rome is at the Council of Lyons (1274). Nevertheless, there are important forms of evidence for the Papal supremacy to be observed in the Acts of 2nd Nicaea, and it is to those observations that a Catholic should be bound to provide explanation for. None of these observed points can be thought to “prove” Papal supremacy or infallibility, but when all the points are taken together, they form what St. John Henry Newman called a “cumulative argument” that arises in favor of something akin to the Petrine primacy that is taught by the Catholic Church, and the same argument, in the opposite direction, recommends less the view of Orthodoxy or Protestantism. Can it be said that all the Byzantines at the time believed in the Roman view of Petrine supremacy? Probably not, but the late French Byzantine historian Charles Diehl was probably correct when he said that the Greeks at the time of the iconoclastic controversy “were ready to acknowledge Roman supremacy and the right of the Roman Church to pronounce final judgment in all ecclesiastical difficulties, provided this would enable them to liberate the Eastern Church from imperial dictatorship.” (Charles Diehl, Byzantium: Greatness and Decline, trans. Naomi Walford (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutger’s University Press, 1957),168).

Response to Objection 1

Some have suggested that the Pope’s description of Petrine authority is an “empty honorific” with “no application whatsoever to reality.” Is that theory well supported? No, and there are solid reasons to demonstrate this. In Pope Hadrian’s epistle to the Emperors, the Pope complains about the Patriarch of Constantinople using the title “Ecumenical Patriarch” in the following words:

“We were astonished that in the imperial injunction you issued concerning the patriarch of the imperial city, namely Tarasios, we find him there called ‘ecumenical’ [patriarch]. We do not know whether this was written through the inexperience of the notaries or the schismatic heresy of wicked men, but we now urge your most clement and imperial authority that he should not be called ‘ecumenical’ in the sequence of your writings, because this is contrary to the regulations of the holy canons and what is laid down by the traditions of the holy fathers. Secondly, save by the authority of our holy catholic and apostolic church, as is patent to all, he never had the right to have this name, since (assuredly) if he were styled ‘ecumenical’ above his superior the holy Roman church, which is the head of all the churches of God, he would manifestly be exposed as a rebel against the holy councils and a heretic. For if he is ‘ecumenical’ he must possess primacy over even the see of our own church which all the Christian faithful will clearly find absurd, because primatial authority everywhere on earth was given by the redeemer of the world himself to the blessed apostle Peter. Through the same apostle (who, though unworthy, we represent) the holy catholic and apostolic Roman church has held till now and will hold for all time primacy and sovereign authority, in such a way that if (which we do not credit) anyone calls him ‘ecumenical’ or assents to this, he should know that he has no part in the orthodox faith and is a rebel against our holy catholic and apostolic church.” (Price, The Acts of the Second Councils of Nicaea 787, 171-72)

From this, three clear reasons stick out against the theory that Hadrian was simply stating empty honorifics for himself.

In the first place, the Pope here is drawing out an error that he thinks is real, and you do not confront something that is real with something unreal. Therefore, Hadrian’s description of Petrine supremacy is, in his mind, factual. As a friend once told me, you don’t correct 2+2=5 with 2+2=3, and so you can’t correct an error with an acclaimed error (in reality). Moreover, there would be no reason to up-play the magnitude of papal power in order to convince Constantinople to disuse a title that makes one sound as if they have a high magnitude of power. If the goal was simply to convince the Patriarch of Constantinople that such titles are wrong, then down-playing Roman power would have been more conducive (i.e. no one should be making such lofty claims). However, Hadrian up-plays the Petrine supremacy of the Roman See, and because this has no intrinsic anti-papal motivations, Hadrian understands the description of Petrine supremacy to be factual rather than exaggerated unreality.

In the 2nd place, if the Byzantines understood the Papal claims of Hadrian to have simply been “empty honorifics”, hyperbolic exaggeration “with no application in reality”, and merely unrealistic literary devices, then they would have had no motivation to remove those claims from the Latin original of the Pope’s letter to the Emperors. It is important here to assert that of the scholarship that believes that Hadrian’s Latin originals were edited and shortened before or during the 2nd Council of Nicaea, most adherents to this theory [minus Anastasius Bibliothecarius himself] believe that the Greeks did this, in part, in order to downplay the claims of Petrine and Roman supremacy (as representative of this, see George Ostrogorsky’s History of the Byzantine State (New Brunswick: Rutger’s University Press, 1969), p. 183-184 and the reference in the footnote 1 of p. 184). But, if we are to rely on this, then it would be a strong force against the theory that either Hadrian or the Byzantines were simply coming across empty self-exalting exaggerations. It is far more likely that, if this retelling of the event is correct, they simply read the text of Hadrian as a factual claim that they simply couldn’t agree with.

In the 3rd place, most scholars do not take the view that Hadrian was producing hollow exaggerations for the sake of literary style, political ploys, or diplomatic games (i.e. wheeling and dealing). I will give just one example here from the renown and award-winning Protestant historian Dr. Karl Morrison, a man who has specialized in the conceptions of authority, tradition, and papal primacy in the 1st millennium with a specialty in Carolingian political thought. This is what he writes concerning Pope Hadrian’s view of the Roman primacy:

“Hadrian contrasted ‘the Church of Constantinople,’ which had converted from error, with the ‘holy, catholic, and apostolic Roman church, which has always held to justice, as it has been written, ‘the see of justice, the house of faith, the hall of uprightness [pudoris].’ ‘The holy catholic and apostolic Roman church,’ he wrote, was the ‘head of the whole world,’ and, since the gates of hell would not prevail against it, the sanctions issued from ‘the most blessed and apostolic See of St. Peter’ must be reverently observed forever by all the faithful. The tradition of the Fathers showed that Rome held that principate over all the earth which Christ granted personally to St. Peter and which that Apostle’s church after him had held and would always retain. The churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch were subject to the ‘Holy, Catholic, and apostolic Roman church.’… Paraphrasing a sentence of Zosimus, Hadrian concluded that all the Church knew that the See of St. Peter had the right to reverse the judgments of anyone, that it had the privilege of judging every church, that no one might judge of its judgment, and that, if anyone presumed to dispute the ruling of the Apostolic See, he was anathema.”

(Karl Morrison, Tradition and Authority in the Western Church, 191-92)

Finally, in the 4th place, When Pope Hadrian responds to the Libri Carolini and its claim that 2nd Nicaea and Rome were in the wrong, the Pope explains that the Apostolic See of Rome has, a priori, always upheld the true faith without blemish, and refers to an inscription that on an old Roman aspe which says “iustitiae sedes, fidei domus, aula pudoris”. This can be translated “The seat of justice, the house of faith, the hall of modesty” (Eng. Trans. J. Toynbee & John W. Perkins, The Shrine of St. Peter and the Vatican Excavations (New York: Pantheon Books, 1957), 233). To refer to the Roman Church as the “seat of justice” and the “house of faith” is to speak of its essence, especially since Hadrian is seeking to use this inscription as a proof text for why Rome is to be defined by its commitment to justice. In fact, it was Charlemagne who thought it was simply “superstition and grossly flattering” to think of Rome as divine justice (c.f. Edward James Martin, A History of the Iconoclastic Controversy, 242). On the contrary, the Pope replied that it was appropriate (ibid.)

Response to Objection 2

Nevertheless, it is perceptively observed by some that, even so, the court theology of Charlemagne likewise speaks highly of the power and authority of the Apostolic See, but nevertheless because they dissented from the Pope on icon veneration and the 2nd Council of Nicaea, this effectively shows that such high claims of Petrine supremacy still amount to having “no application in reality” and are “effectively meaningless”. Well, the proof against this so far as the Pope himself was concerned provided above appears to me as conclusive, and so whatever we find in the court theology of the Carolingians is a separate matter, but nonetheless a matter worth looking into. At this time, one of the most prestigious Western scholars of theology, philosophy, and Church law was St. Alcuin of York, and it was he that became the most influential scholar of Charlemagne’s court theologians. He is believed to have written the Libri Carolini (the Caroline Books) which is the locus for the data that supposedly shows that the Petrine supremacy of Rome was basically nothing when “the rubber meets the road”. If there is anyone to show what might have been the Papal thought amidst Charlemagne’s court, it would be St. Alcuin. In a letter to a pupil priest Oduin (and spread abroad), he writes the following concerning the importance of orthodoxy and Church membership:

“You see how faithfully, how reasonably, and prudentially all these things have been handed down for our observance. Let no Catholic dare to assail the authority of the Church (ecclesiae auctoritatem); let no sane person dare to attack a custom that is reasonable; let none of the faithful fight against the mind of piety. And lest he be found a schismatic, and no Catholic at all, let him follow the most approved authority of the Roman Church (Romanae ecclesiae auctoritatem),that whence we have received the seeds of the Catholic faith there we may find the exemplars of salvation, lest the members be severed from the head, lest the key-bearer of the heavenly kingdom exclude such as he shall recognize as alien from his teaching.”

(Monumenta Germaniae Historica 1895, Epistle IV, p. 215; Eng. Trans. Gellard Ellard, S.J, Master Alcuin, Liturgist (Chicago: Loyola University, 1956), 82; H.I.D. Ryder, Catholic Controversy: A Reply to Dr. Littledale’s ‘Plain Reasons’ (New York: The Catholic Publication Society, 1886), 80.

In exercising what we call one of the spiritual works of mercy, i.e. admonishing the sinner, St. Alcuin puts communion with the Roman Church as indispensable for salvation, right alongside the authority of the Church, the mind of piety, and the exemplars of salvation. This is a context of plain speech, and thus what he thinks is factual data.

Elsewhere, he writes:

“Power is divided between the spiritual and temporal powers; the latter must be the defenders of the former, and, as such, are instruments of vengeance rending their adversaries and punishing the wicked for their evil deeds; whereas the spiritual, full of saving grace and power, doth open the portals of heaven to the faithful and doth give joy never ending to the good”

(MGH, Epistle XVII, p. 48; Eng. Trans. Rolph Barlow Page, The Letters of Alcuin (New York: The Forest Press, 1909), 41.

Further:

“Hitherto, there have been three powers, pre-eminent above all others. First of all, there is His eminence the Pope, the Vicar of Christ, who, though even now most grievously ill-treated (as we know from your letter), is wont to rule as the successor of Peter, the Chief of the Apostles. In the second place, cometh the head of the secular powers, the Emperor, who of late, as everyone knoweth, hath been most impiously deposed by his own people. In the third place, there is the royal power, to which dignity hath pleased our Lord Jesus Christ to elevate thee, vouchsafing thee more power, more wisdom, and more glory than the other two potentates.”

(Rolph Barlow Page, Op. Cit., 42).

Therefore, for St. Alcuin, the Papal administration of the universal Church was the first spiritual power (potestas) governing the whole world in the person of Peter’s successor and his “rule”. Such cannot be an empty honorific since it is articulated plainly the concrete

realities such as the Imperial and Royal administration of the secular world. For him, the potentate of the Roman papacy was an authentic spiritual power just as real as the temporal authority. None of these descriptions were made in the context of diplomatic advantage, and so “empty honorifics” cannot be applied. When speaking to the “rules” or “canons” of the Christian religion, as drawn from Morrison’s book (p. 162), St. Alcuin numbers them in this order:

- The 4 synoptic Gospels

- Apostolic letters

- The confession of the whole Church

- Preaching of the Roman Church

Therefore, the faith of the Roman Church is a “rule” or “canon” of the Christian religion right underneath the infallible rules of Scripture and the unanimous consent of the Fathers. That suggests that Rome, in St. Alcuin’s mind, is more than just another Church that has supreme canonical privilege. Rather, this is a divine establishment in his understanding. Even more obvious is that the preaching of Rome is an empty flattery or honorific since it is being ranked with divinely infallible sources.

Still more corroborative evidence exists. When Pope St. Leo III was accused of both perjury and adultery, Charlemagne convened a Roman synod in on December 1st, 800 to investigate the charges. This synod included members of the Frankish episcopate and Roman nobles. Of the Franks, there were many associates who were reared by the beliefs of St. Alcuin such as Arno of Salzburg and Theodulph of Orleans. The fathers of the council referred to the principle Apostolica sedes a nemine iudicatur (the Apostolic See is judged by no one), and simply had the Pope issue a denial of the charges. They wrote:

“We do not dare to judge the Apostolic See, which is the head of all the churches of God. For all of us are judged by it and its Vicar; it however is judged by nobody as it is the custom from ancient times. But as the highest Pontiff will have decided we shall obey canonically”

(Luitpold Wallach, “The Roman Synod of December 800,” in Diplomatic Studies in Latin and Greek Documents from the Carolingian Age, ed. Luitpold Wallach (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 339)

That the Council followed Alcuin’s understanding is clear from a letter from Alcuin to Arno of Salzburg approximately 1 year before the Roman synod:

“… the Apostolic See is to judge, not to be judged… What pastor in the Church of Christ can be safe if he who is the head of the chuches of Christ is cast down by evil doers?”

(MGH, Epistle 179, p. 297; Eng. Trans. Karl Morrison, Tradition and Authority in the Western Church 300-1140 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 161.

Therefore, when Alcuin says the following in his letter to Pope Hadrian I, it should be understood as an honorific, but not an *empty* honorific, but one rooted in reality, and divine reality at that:

“I know that by enrollment of holy baptism I belong to the fold of that shepherd who shrank not from laying down His life for His sheep; and these He entrusted to the pastoral care of blessed Peter, prince of the apostles, for his thrice-repeated declaration of great love; on him the Lord bestowed in heaven and earth an eternal power of binding and loosing; and of his holy see, most excellent father, I recognize you as the Vicar, and confess you to be the heir of his wondrous power”

(Alcuin to Pope Hadrian I; Eng. Trans G.S.M Walker The Growing Storm: Sketches of Church History from A.D. 600 to A.D. 1350, 45).

Here, St. Alcuin clearly says that the Bishop of Rome is the “heir” of the “wondrous power” given by Christ to Peter. That is simply what we mean by divine institution. It just so happens that Alcuin expands upon this notion in another epistle, this time to Bishop Felix of Urgel, with an attempt to convince him away from the adoptionist heresy, he says the following:

“‘Where is the power given to Peter, the prince of the Apostles: ‘Thou art Peter and upon this rock I shall build my Church’ etc? Has this power been taken from him and transmitted to you, to the end that upon you, at the end of time and in a corner of the world, a new Church might be built disagreeing with the apostolic traditions?’ He urged Felix to return to the fold which Christ commended to St. Peter.”

(MGH, Epistle XXIII, p. 60; citation from Morrison, Op. Cit. , 162).

In the context, St. Alcuin explicitly mentions the confession of the Roman Church as the confession Felix must resort to for a return to orthodoxy, clearly signifying that the Roman Pontiff is the shepherd entrusted with pastoring the universal sheepfold of Christ. It seems clear that Alcuin, the chief theologian of the court of Charlemagne understood the Apostolic See of Rome as the unique inheritor of the singular prerogatives given to St. Peter by Christ, that all who broke communion with Peter’s successor were in schism, and that no power on earth could judge the Pope, but that only he, as the universal head, could be the judge others. This is all within the context of plain language where flattery and honorifics have no function. It is obvious, therefore, that the chief theologian of Charlemagne’s court could hardly be described as one who did not believe in the divinely established primacy of the Apostolic See. But what about the fact that the Caroline Books include rejections of the doctrinal pronouncements of Pope Hadrian?

In the Libri Carolini, again, probably written by St. Alcuin, Charlamegne himself brings into view the divine pre-eminence of the Roman Church as one of the reasons for why he rejects the Council of Nicaea (787). This is not found in the preface or in an epilogue, but rather one of the articles in a long list each of which seeks to defend the Frankish rejection of icon veneration. Charlemagne, or his court theologian(s), wrote:

“The Church of Rome is above the rest and must always be consulted on matters of faith. Scripture and doctrine are authenticated by Rome.”

“Quod sancta Romana, catholica et apostolica ecclesiae caeteris ecclesiis praelata pro causis fidei, cum quaestio surgit, omnio sit consulenda.”

(Libri Carolini 1.6; Eng. Trans. Edward James Martin, A History of the Iconoclastic Controversy, 237)

Again, this was one of the reasons in a long list for rejecting 2nd Nicaea and the Pope’s own confession on the veneration of images. Therefore, while it is true that the court of Charlemagne was prepared to dissent from what the Greeks called the 7th Ecumenical Council (for the Pope did not call it so), it is more than obvious that Charlemagne still believed that the magisterium of the Apostolic See was indispensable to the dissemination of authentic doctrine. This was not the context for an “empty honorific” precisely because Charlemagne (and his court theological writer(s)) is using the principle of Roman authority to refute the current occupant of the Roman See! However, the theologians of Charlemagne’s court believed that the tradition of the Roman Church was so indispensable that a current occupant of the Chair of Peter would have to be called into account if they were particularly at variance with their predecessors and dissented from if he chose to break from the inherited tradition of Rome. This is an early instance of what is today called the “recognize and resist” posture, i.e. one recognizes the divine placement of the Roman Pontiff while resisting his fallible judgments. In Charlemagne’s case, he thought that the Franks were more in line with the antique Roman tradition than the current papal occupant, Hadrian. Due to the plain language and function of the appeal to the indispensability of Rome in the Caroline Books, the honorific language could hardly be described as “empty” since it was precisely the binding force of the Roman tradition that led Charlemagne to dissent from Pope Hadrian’s support of venerating icons.

Response to Objection 3

It has to be remembered that the confiscation of these territories from the Roman Patriarchate (regional supervision) was an Imperial transgression, and the Pope never asked the Council to return the patrimonies nor the jurisdiction of these lands, but specifically the Emperors. In both his letter to the Emperors and even in his letter to Tarasios, the plea is for the Emperors to undo this illegal confiscation of Roman property.

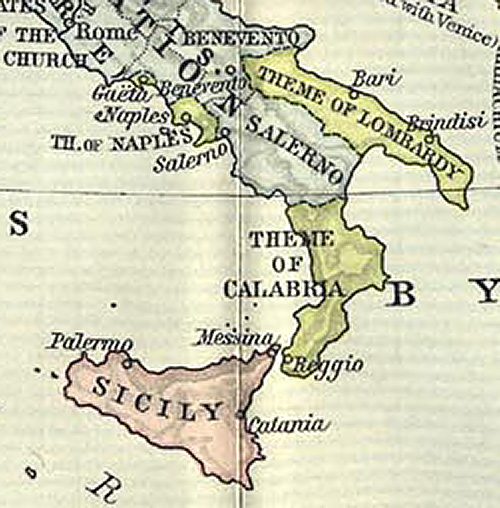

A bit of historical background is in order. When the Byzantine Emperor Leo III came into Imperial office, he demanded that Rome follow the iconoclastic policy of Constantinople. Pope Gregory II and his successor Gregory the III rejected this, and the latter held a Roman synod wherein all who destroy images are excommunicated by the authority of Peter. In 733, as a punishment to the Pope, Leo III confiscated the Papal patrimonies in South Italy and Sicily, cutting off funds that went to Rome to sustain candles and for the distribution to the poor. The same Emperor unlawfully confiscated Rome’s Patriarchal supervision of the churches in Calabria, Sicily, and prefecture of Illyricum (Thessaloniki, Macedonia, and Greece). These churches were then put under the Patriarchal oversight of the heretical and iconoclastic Patriarchate of Constantinople. If Rome had continued to try and supervise these churches, they would have been met with military opposition.

This effectively divided the Byzantine East and the Latin West. When Empress Irene decided to turn things around, it was then that the Pope requested that the Imperial administration undo the illegal confiscation of territories the iconoclast Leo III. In all likelihood, the bishops at the Council of Nicaea 787 left this up to the Emperors to decide, seeing it as something outside of the power of the Council. This was the excuse used at the Council of 879-90 when the bishops had no problem conceding these the prefecture of Illyricum, then particularly in the region of the Bulgars. The Byzantines quite literally thought that the division of ecclesial jurisdiction along Imperial borderlines was outside the hands of a Church Council and was a decision for the Emperor to make. Pope Hadrian did not hear anything back on this matter from the Council of Nicaea 2 nor the Emperors, and we get his reaction from a letter he wrote to Charlemagne on the matter:

“We have made as yet no reply to the Emperors, fearing they may return to their error. We exhorted them long ago about the images and the dioceses of the archbishops which… we sought to restore to the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Roman Church, which they sequestered together with our patrimonies at the time they overthrew the holy images. To those exhortations, they never replied. They have returned in one point from their errors, but in the other two they remain where they were [i.e. the dioceses of south Italy and the patrimonies]… If your God-protected Royal Excellency agrees we repeat our exhortation [to Constantinople], expressing gratitude that the holy images are in their former state. But as to the dioceses of our holy Roman churches… and the patrimonies we warn the Emperor solemnly that if he does not restore them to our Holy Roman Church, we shall decree him a heretic for persistence in this error.”

(Mansi 13.808; Eng. Trans. Edward J. Martin, A History of the Iconoclastic Controversy, 250).

It should be recalled that the Pope never ratified the Council “as Ecumenical” because of the lack of co-operation of the Emperor to satisfy his request of the confiscated territories. He did accept its policy and doctrine on images. In any case, it would be slightly misleading to think that the Council of Bishops simply ignored the Pope’s demand. As Fr. Richard Price remarks, “For it was not Tarasios but the emperor who was to blame for the failure to restore the jurisdiction and patrimonies” (Price, Acts of Nicaea 2, 67). Some Orthodox might press the matter that if the Pope had universal jurisdiction, he would not have to ask for something that already belongs to him. However, this stance ignores the difference between the Patriarchal supervision that Rome had over unique lands and the universal Petrine commission which worked through the mode of appellate procedure. Aside from this, it should be recalled that Pope St. Nicholas I and Pope John VIII, both strong proponents of universal jurisdiction, also requests the return to the patrimonies of Sicily and Calabria, and jurisdiction in Illyricum. At that point in time, Photius himself explicitly said that he would agree to do so, but that the Emperor vetoed that decision and was entirely out of the Church’s hands. It may be legitimately questioned whether the Emperors believed the Pope had jurisdiction over the whole Church. To this we should remind ourselves that the Byzantine East had just finished a long career in iconoclasm and then, just some decades later, most Eastern bishops (Price, 62), together with a new Emperor (Leo V), iconoclasm was back on the menu for even more decades. It is enormously obvious, therefore, that many of the Eastern Bishops and Emperors did not believe the Pope was divinely authoritative in commanding them to do this or that. For that matter, they also did not believe Nicaea 2 had any authority over them. Emperors and Bishops didn’t even feel bound to hold to what their immediate predecessors held, seeing as when the 2nd wave of iconoclasm came, the Byzantines rehabilitated the ecumenical status of Hieria (754)!

Lastly, let’s venture out with the Orthodox polemicist on the thin limb in considering this question of why the Eastern Bishops felt that the return of episcopal boundaries from Constantinople to Rome was ultra vires to ecclesiastical authority, and let’s admit that this shows that they didn’t hold the Pope had universal immediate jurisdiction. What actions are proven in its place? Is it the Eastern Orthodox policy of sobornost conciliarity that takes the place of Papal supremacy? No. What is there is Imperial supremacy. And so, if the Orthodox polemicist wishes to execute a silver bullet refutation to Papal jurisdiction by this whole matter of the Western patrimonies and the prefecture of Illyricum, they might just prove a doctrine of Imperial supremacy which likewise would cut through the official position of both Catholicism and Orthodoxy. On top of that, they will have to figure out precisely what doctrine delivered by Christ it was that teaches how the secular government can arise to levels of power over the Church’s spiritual society. And if such an organ did arise to such an essential part of the Church’s society so as to manage its internal affairs of doctrine and jurisdiction (for that it no less than what Leo the Isaurian claimed), then where did this divinely established organ go after the fall of Constantinople in 1453?

Response to Objection 4

The Catechism of the Catholic Church understands the text of Matthew to refer to the universal Church. That is precisely why the Apostle Peter, in his successor, has a pastoral reach towards all Christians everywhere. As such, the Church whose episcopate retains the presidency of Peter is the ongoing function of the rock that protects the Church from. But if you notice the nature of the relationship between Peter and the universal Church, you’ll notice that it is Peter who is designated as the object of support, strength, and protection. That is what foundation rocks do for the building erected on top of it. So, if here the universal Church is indefectible from the gates of hell, then that is because there is the rock which upholds the church which has cannot be overcome by the gates of hell.

Response to Objection 5

The Code of Canon Law state the following:

Can. 339 §1. All the bishops and only the bishops who are members of the college of bishops have the right and duty to take part in an ecumenical council with a deliberative vote.

Can. 341 §1. The decrees of an ecumenical council do not have obligatory force unless they have been approved by the Roman Pontiff together with the council fathers, confirmed by him, and promulgated at his order.

The belief at the time that all the Patriarchs needed to be involved in a Council for it to be truly “great and Ecumenical” was a belief simply driven by the rule that the whole Church should be joining in one voice to proclaim the Apostolic faith, as opposed to a part of the Church doing so. The Council Hieria (754), which only involved a part of the Church, sought to speak on behalf of the whole. Such can’t be a great and ecumenical council. However, during a Council, the Apostolic See of Rome has “chief place” in the primacy and legitimacy of a valid Council representing the universal Church. In the 7th session of 2nd Nicaea, it is said that it is the “law of Councils” for the Roman Pontiff to have “sunergeia” (co-operation) together with an Episcopal gathering. This co-operation was detailed to be effective either through “representatives” or an “encyclical letter”. History showed this in the action of Rome at the Councils of Ephesus (431), Chalcedon (451), and Constantinople III (681). That is the standard operating procedure. Of course, simply having Papal legates and an encyclical letter would not be sufficient to host a universal gathering. It must also have the “assent” of the universal face of the Church which was embodied in the Eastern Patriarchs and their synodal units under them. Today, that might look drastically different since the Church has far expanded the confines of Imperial Christendom, let alone Roman-Byzantine Christendom. The contemporary Eastern Orthodox fixation upon the Pentarchy illustrates not only that their ecclesial bodies are stuck in the temporary and secular construct of the Middle Ages, but also that they have become encrusted in a system of thought which cannot be reproduced. This lends towards an overall paralysis in having a coherent administration, and the world is beholding that as each generation goes by.

We get further confirmation of Rome’s chief influence in Councils in the 3rd session of 2nd Nicaea. It was known that, just like at the 6th Council, the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem could not make it to the Council due to the hindrance created by Arab occupation and persecution. It was stated that, in place of their presence, there would be 2 “synkelloi” which means the “principal assistants” of the Patriarchs (Price, 199, fn. 6). These 2 would stand in the Council and speak for all 3 Patriarchs to fulfill their “assent” to its decrees. For if only Rome and Constantinople were truly present at the Council, this calls into question the potential of 2nd Nicaea to achieve an ecumenical status when 3 out of the 5 Patriarchs were not there! One letter on behalf of the Eastern Patriarchs anticipated this and even pressed on that, despite their absence, the bishops should not “be offended by the absence of the most holy patriarchs of the three apostolic sees and the most sacred bishops under them” (Price, 219). Well, what did they offer in place of their absence that would ensure 2nd Nicaea could achieve ecumenical status? They go on in the letter to say that their absence should not hinder the Council “especially since the most holy and apostolic pope of Rome has expressed his agreement with it and is cooperating through his apocrisiarii. And now, most holy one [Tarasios], may this take place with God’s help. Just as then the faith of that council resonated to the ends of the world, so now, through your help and that of the one who directs the apostolic see of the chief of the apostles, the faith of the council about to assemble by the grace of Christ will be proclaimed in the whole world beneath the sun…” (Price, 220). In other words, whatever handicap the absence of the 3 Eastern Patriarchs and their under-bishops might surface to discredit the Council, the co-operation and agreement of the apostolic see of Peter is a sufficient weight to make their absence negligible to actually discredit the Council.

Such shows that Rome had the principal place at the convocation and authority of Councils. The Byzantine understanding of the requisite nature of the Roman Pontiff in Ecumenical Councils was succinctly stated by St. Nikiphoros, Patriarch of Constantinople (758-815). On the authority of 2nd Nicaea, he says the following:

“This Synod possesses the highest authority… In fact it was held in the most legitimate and regular fashion conceivable, because according to the divine rules established from the beginning it was directed and presided over by that glorious portion of the Western Church, I mean by the Church of Ancient Rome. Without them [the Romans], no dogma discussed in the Church, even sanctioned in a preliminary fashion by the canons and ecclesiastical usages, can be considered to be approved, or abrogated; for they are the ones, in fact, who possess the principate of the priesthood and who owe this distinction to the two leaders of the Apostles.”

(Nikiphoros, Apol. pro sacris imaginubus 25 (PG 100.597A); as quoted by Francis Dvornik, Byzantium and the Roman Primacy, 96; amended translation and citation obtained from Monsignor Paul McPartland, A Service of Love: Papal Primacy, the Eucharist, and Church Unity (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2013), 69.)

Could it be any clearer? This Byzantine Saint appeals to the supreme status of a Council only on certain conditions and rules. Those rules he calls “divine rules established from the beginning”. In other words, these are not human made rules, such as from canons and discipline. Rather, these rules are from “the beginning”. What beginning? The 4th or 5th centuries? No, this beginning is referring to the time when the Apostles stood in the flesh before men on earth, for St. Nikiphoros roots the distinguished authority of Rome from the dual source of St. Peter and St. Paul, the two founding architects of the Roman Church. Therefore, he means the Apostolic beginning. The nature of Rome’s authority is stated to be indispensable, and that no dogma can be considered ratified or annulled without the sanction of the Roman Pontiff.

It might well be asked to the contemporary bodies that claim lineage to the Byzantine Orthodox Churches whether they have lost the means to do precisely what St. Nikiphoros here states would be impossible without the Pope of Rome according to divine prescription. If not, they would have to say they have lost something which was understood, well before the end of the 1st millennium, to be an Apostolic design embedded into the very architectural plans for the Church, without which they cannot settle dogmatic matters. We might well respect the efforts they claim by a mutual agreement to assemble under their Primate, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, in a pan-Orthodox Synod, but that would be from a different principle and procedure than what St. Nikiphoros here spells out rather clearly.

Lastly, it seems fitting to also point out that St. Nikiphoros is speaking in a context wherefrom he is committed to defending the lasting authority of 2nd Nicaea. Consequently, his comments on the pre-eminence of the Apostolic See are in a context wherein “empty honorifics” would work contrary to his goal. Therefore, his words are to be taken in plain language.

Response to Objection 6

In this rebuttal, it is going to be presumed, for the sake of argument, that the Greek version that came to be in possession of the East of Hadrian’s letter to the Emperors is that real authentic conciliar text. It will be insisted that even if this were the case, it is just as powerful, perhaps even more, than the Latin original of the same letter. Modern day Orthodox polemicists think that by the inclusion of both Peter and Paul, and that the pastoral commission to overpower the Church was given to those who succeed to the “thrones” (plural) of the chief Apostles, the Vaticanal theory of Roman primacy is undercut and refuted. However, such cannot be the case. The Greek sentence wherein it speaks of the thrones of the Apostles is as follows:

Αὐτοὶ γὰρ οἱ ἅγιοι καὶ κορυφαῖοι τῶν ἀποστόλων οἱ τὴν καθολικὴν καὶ ὀρθόδοξον πίστιν ἐναρξάμενοι ἐγγράφως ἐθεσμοθέτησαν τὴν αὐτῶν πίστιν κρατεῖν πάντας τοὺς μετ’ αὐτοὺς διαδόχους μέλλοντας γίνεσθαι τῶν θρόνων αὐτῶν καὶ ἐν αὐτῇ διαμένειν ἕως τῆς συντελείας. (Mansi 12.1058)

“For the holy and chief Apostles themselves, who set up the Catholic and orthodox Faith, have laid it down as a written law that all who after them are to be successors of their seats, should hold their Faith and remain in it to the end.”

When it says τῶν θρόνων αὐτῶν (their seats, or more literally, their thrones), we must look at what “their” (gentive) is referring back to. In the context, this “αὐτῶν” (their) is a genitive (of origin) referring back to the subject of the sentence, which is οἱ ἅγιοι καὶ κορυφαῖοι τῶν ἀποστόλων (the holy and chief Apostles). Therefore, these thrones are not the thrones of any bishop, but specifically the thrones of Peter and Paul, which are strictly related to the Roman Church in the context. Here’s why. The section prior to this sentence (which will be pasted below) shows that it is the Pontiff of the Roman Church who is uniquely described as the “Vicar” of Peter and Paul, and thus the inheritor of their power, and that the Imperial administration will be sure to obtain prosperity if it were to follow the tradition of the Vicar of Peter and Paul, because that Vicar, who occupies their thrones, is guaranteed to maintain their same faith until the consummation of history. The whole argument is centered on the benefits that come with following Rome and its bishop (the Vicar of Peter and Paul), and to introduce the idea that “thrones” is pertinent to every bishopric is alien to the context and at variance with the argument being made.

“And especially if you follow the tradition of the orthodox Faith of the Church of the holy Peter and Paul, the chief Apostles, and embrace their Vicar, as the Emperors who reigned before you of old both honoured their Vicar, and loved him with all their heart: and if your sacred majesty honour the most holy Roman Church of the chief Apostles, to whom was given power by God the Word himself to loose and to bind sins in heaven and earth. For they will extend their shield over your power, and all barbarous nations shall be put under your feet: and wherever you go they will make you conquerors. For the holy and chief Apostles themselves, who set up the Catholic and orthodox Faith, have laid it down as a written law that all who after them are to be successors of their seats (θρόνων / thrones), should hold their Faith and remain in it to the end.”

The context is strongly suggestive that “thrones” is simply referring to the dual-authority and dual-position of Peter and Paul that their “Vicar” occupies, i.e. the Bishop of Rome. The reader might be tempted to think that the plural of thrones must entail that the meaning is more than one subject occupying each of the thrones, but the context refers to the single bishop of Rome as the “vicar” of Peter and Paul, and the inheritor of the “power” given to both. And so, it must be that the single person of the Roman Pontiff inherits the “thrones” of both Apostles. With this interpretation, the meaning of the Greek version is quite straightforward. Put simply, the Roman Empire will find prosperity in following the Church and Vicar of Peter and Paul, to whom was given the power of the keys, because that Church (i.e. Rome) and its Vicar (i.e. the bishop of Rome) is guaranteed by a “written law” to maintain the faith of Peter and Paul all the way until the end of time. Ergo, if the Roman Empire follows Rome, it will prosper until the end of time. Implied here is the supreme power given to the Apostolic See and a bold claim to its perpetual infallibility. The idea that “their thrones” is supposed to be a message about all bishops anywhere, be it Corinth, Thessaloniki, York, Carthage, Antioch, Ephesus, et. al., is an extremely far-reaching interpretation that can almost reveal an anti-Roman bias, and therefore lacking in credibility.

As for the inclusion of St. Paul together with St. Peter. Prima facie, this doesn’t reduce the power of the message since it is stated that both Apostles were given the “power” of the keys of the kingdom, and that this has, in a special way, been inherited by their Vicar, the president of the Roman Church. Therefore, while the Orthodox polemicist would want to see in this a flattening out of Church authority such that by having 2 Apostles in view, all bishops must also be in view, the opposite is in fact the case. The letter’s intention is still to individuate the Roman Church and its ability to be a conduit of blessing and prosperity to the Roman Empire by its fidelity to Christ through being faithful to Sts. Peter and Paul, and the latter is done by being faithful to their Vicar.

Response to Objection 7

This is the translation of the original Latin of Hadrian’s letter to the Emperors which is the center of debate on the matter of the Council’s rejection of the Papal claims.

“If, moreover, following the traditions of the orthodox faith, you embrace the judgement of the Church of the blessed Peter, prince of the apostles and, as the holy emperors your predecessors did of old, so you too venerate it with honour and love his vicar from the depths of your hearts, or rather if your rule granted by God follows their orthodox faith in accordance with our holy Roman church, the prince of the apostles, to whom was given by the lord God the power to bind and to loose sins in heaven and on earth, will repeatedly be your protector and strew all the barbarian nations under your feet, parading you everywhere as victors. For sacred authority reveals the marks of his [Peter’s] dignity and how veneration should be paid to his supreme see by all the faithful throughout the world. For the Lord appointed him, as key-bearer of the kingdom of heaven, to be prince over all, and honours him with the privilege by which the keys of the kingdom of heaven were entrusted to him. And so, elevated by this supreme honour, he was worthy to profess the faith on which the church of Christ is founded. This blessed profession was followed by the blessing of a reward; it was by his preaching that the holy and universal church was made illustrious, and it was from it that the other churches of God receives the proofs of the faith. For the blessed Peter prince of the apostles, who was the first to preside over the apostolic see, left the primacy of his apostolate and pastoral responsibility to his successors, who are to sit in his most sacred see for ever. The power of authority, as it had been granted to him by the Lord God our Saviour, he in his turn conferred and transmitted by divine command to the pontiffs who succeeded him, in whose tradition we venerate the sacred effigy of Christ and the images of his holy mother, the apostles and all the saints.”

(Hadrian to Emperors, 2nd session of Nicaea 787, in Price, p. 157)

Basic message – If the Imperial government of the Roman Empire harkens and follows the authority of the Roman Church by following his Vicar, St. Peter will in turn protect and augment the success of the Empire.

Papal claims

- Christ singled out Peter and set him up as the universal head of the Church by entrusting to him the possession of Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven.

- The Episcopal chair of the Roman Church succeeds perpetually to the universal headship of Peter over the whole church. [Supremacy and infallibility strongly witnessed]

Orthodox critics of the Catholic doctrine of the Papacy will try to show here that the above was far too unacceptable for Byzantine ears, and so it was edited, and the Greek version was the resulting message accepted by the Council. However, here is the translation of the original Latin of Hadrian’s letter to Tarasios which has no editing in the Greek version (they match perfectly):

“May all the weeds be uprooted from the church, and pray the word [promise] of our Lord Jesus Christ be fulfilled, that ‘the gates of hell will not prevail against it,’ and further, ‘You are Peter, and on this rock I shall build my church. And I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; and whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven , and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven,’ His see [throne] shines forth as primatial throughout the world and is the head of all the churches of God. Therefore the same blessed Peter the Apostle, shepherding the church at the command of the Lord, has left nothing to neglect, but upholds, and has always upheld, her authority.” (Hadrian to Tarasios, Ibid., 180)

Basic Message: Hadrian calls upon the promise of Jesus that the Catholic Church would be protected from the gates of hell and that the investiture of power given to St. Peter would come to provide the means of that protection.

Papal Claims: The investiture of power given directly from Christ to Peter is singularly inherited by the bishopric of the Roman Church, and it is through this means that Peter continues perpetually to govern the Church by the divine vocation of Christ our God Himself. [supremacy and infallibility is strongly witnessed].

One can see, therefore, that there is no substantially different message between the Papal claims of the letters sent by Hadrian to 2nd Nicaea, and so this completely removes any motive on the part of the Council to water-down the Pope’s claims to divine and perpetual Petrine supremacy. Effectively, this last point makes the observed differences between the famous section of the Latin original of Hadrian’s letters to the Emperors and the survived Greek copy completely irrelevant to the question of how 2nd Nicaea understood papal authority. Even Anastasius Bibliothecarius himself, when commenting on the motivations behind the observed differences between the Byzantine-Greek codices of 2nd Nicaea and the Latin version, only finds the Greeks seeking to omit any offensive passages that would insult the election of Tarasios of Constantinople, or of Photius of Constantinople (if one follows the scholarship of Erich Lamberz and Luiptold Wallach). In addition, in this view, they only additionally remove the request of the Pope to return the confiscated patrimonies and Patriarchal jurisdiction to Roman management. Not a single peep from Anastasius that the Greek version is the result of Byzantines rejecting the Papal claims of Pope Hadrian. It is far more likely, then, that the contemporary debate between Catholics and Orthodox on the Greek editing of Hadrian’s original Latin letter to the Emperors is an invention of Orthodox polemicists, and has no roots in the actual history of the manuscript transmission. If what is written above is not sufficient to settle this matter, one could easily find corroborating evidence in the manuscript situation of the Council of Constantinople 879-80, which is considered by many Orthodox as the 8th Ecumenical Council, and still authoritative even if not. In that council, the bold proclamations of universal jurisdiction are left plain as day in both Latin and Greek, and under the supervision of no less than Photius the Great.

Just wanted to let you know that scholars now regard Theodulf of Orleans as the author of the Libri Carolini / Opus Caroli. Alcuin may have had some hand in it but its uncertain. What is certain is that Theodulf was its primary author.

As for II Nicaea and icons in the Latin West, you wanna check out Thomas F. X. Noble’s Images, Iconoclasm, and the Carolingians. Really good book.

*may wanna check out* – sorry was typing on my phone.

I should also add, Noble in his book does discuss the issue of papal primacy in that book I mentioned above, both vis-à-vis Charlemagne’s court as well as the court of Irene and II Nicaea. You might find it interesting. It’s a fairly nuanced take he offers, especially with Charlemagne’s court, imo.

As for Theodulf’s particular views on papal primacy, I suppose I will offer a few rudimentary remarks – as it has been a long time since I read his work, so anything I say here on the content of his theology is quick and dirty. Theodulf was from Iberia, which also happened to be a source of another doctrinal controversy – Adoptionism. Now, as I found in John Cavadini’s book The Last Christology of the West, it appears that those who emphasized papal authority were the Adoptionists, while their Iberian opponents who would gain the support of the Franks and Rome, did not like that idea. What that means entirely, I am not sure – but it probably indicates that Theodulf at least came from a religious milieu that did not invest a lot of stock in papal authority. Maybe I am wrong.

Beyond Noble’s book, however, if you wanted to dive into the weeds of Theodulf, I would recommend Ann Freeman’s Theodulf of Orleans: Charlemagne’s Spokesman against the Second Council of Nicaea (2003). It is a collection of articles she wrote over her career on Theodulf and remains fundamental.

As for Theodulf’s work itself, unfortunately not much has been translated. I have his poems in translation in pdf format, if you would like. Not sure it would help you much, should you be interested. One of the poems includes and epitaph he wrote for Pope Hadrian I upon his death.

Hi Alura,

Thanks for the recommendation. I have not finished Nobles, but what I have read is extremely well. I have also gone through his course on the Papacy in History. Great teacher.

This post was actually a response to the anti-Papal revisionism that was shown by an Orthodox polemicist Craig Truglia in his debate with James Likoudis. I thought they were good enough objections to be standard polemics.

Yes, I understand it was initially a response to Truglia. I merely wanted to point out the Alcuin/Theodulf issue for its own sake. I am not in the habit of dealing much with apologetics anymore, so I don’t tend to keep up with the authors of any given debate all that much – especially the papacy.

Completely understand. Thank you for the pointer

Hey Erick. Thank you for the article. I guess you forgot to mention whether or not this part is present in the Greek version of Pope Hadrian I’s first letter to the council on Suan’s channel. could you please address it? or perhaps you did and I missed it.

“We were astonished that in the imperial injunction you issued concerning the patriarch of the imperial city, namely Tarasios, we find him there called ‘ecumenical’ [patriarch]. We do not know whether this was written through the inexperience of the notaries or the schismatic heresy of wicked men, but we now urge your most clement and imperial authority that he should not be called ‘ecumenical’ in the sequence of your writings, because this is contrary to the regulations of the holy canons and what is laid down by the traditions of the holy fathers. Secondly, save by the authority of our holy catholic and apostolic church, as is patent to all, he never had the right to have this name, since (assuredly) if he were styled ‘ecumenical’ above his superior the holy Roman church, which is the head of all the churches of God, he would manifestly be exposed as a rebel against the holy councils and a heretic. For if he is ‘ecumenical’ he must possess primacy over even the see of our own church which all the Christian faithful will clearly find absurd, because primatial authority everywhere on earth was given by the redeemer of the world himself to the blessed apostle Peter. Through the same apostle (who, though unworthy, we represent) the holy catholic and apostolic Roman church has held till now and will hold for all time primacy and sovereign authority, in such a way that if (which we do not credit) anyone calls him ‘ecumenical’ or assents to this, he should know that he has no part in the orthodox faith and is a rebel against our holy catholic and apostolic church.”

is this portion present in the Greek version of the letter?

I believe it was in the original Latin and Greek. For the arguments for this, see the article I wrote on the Latin and Greek versions of Hadrian’s letters.

Pingback: Response to Ybarra on Nicea II – Orthodox Christian Theology

Pingback: Final Exchange on 2nd Nicaea | Erick Ybarra

Pingback: Dr. Frederico Montinaro & Richard Price on Pope Hadrian I’s Letters to Emperors: Read Full at Council of Nicaea (787) | Erick Ybarra

This is excellent ammo against the Russian Schismatics!